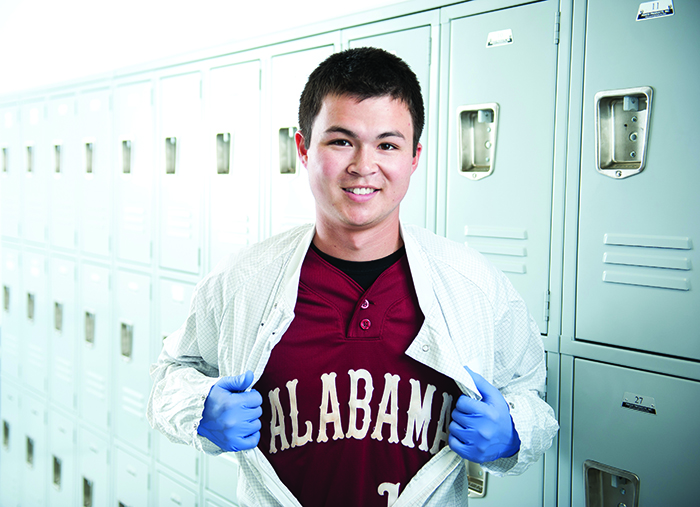

Michael Carton joined the Alabama Club Baseball team his sophomore year at The University of Alabama, but he’s played the sport competitively since his T-ball years. He enjoys the travel and has played with the team in states across the South, including Louisiana, Tennessee and South Carolina. Then there’s the main reason he plays: “I think, honestly, I just like hitting the ball.”

With night practices and weekend games, he sees a lot of his teammates. But most of them probably would not recognize Carton if they saw him at work.

Disguised in a plastic jumpsuit, breathing mask, hairnet, plastic gloves and disposable boots, Carton blends in well at UA’s Micro-Fabrication Facility, where he works as an undergraduate research assistant. Also called the clean room, this is the lab where UA researchers create tiny structures needed for solar cells, semiconductor chips, computer disk drives, advanced memory and various nanosensors and detectors.

“The scale of the devices we work with is so small that any dust or particulate can completely destroy them,” Carton said.

Even for a task as simple as note taking, researchers must use the lab’s specially made notebooks, which are designed to resist dust particles.

Carton, a senior from San Diego, California, studying metallurgical and materials engineering, works alongside graduate students in the lab to produce thin films. To make the films, lab workers deposit a series of metals and compounds onto a blank silicon disk – a thin circular slice of semi-conductor material that looks like a tiny vinyl record. The order and thickness of the compounds deposited determines the function of the films. Afterward, the data collected by the graduate students is used by companies like Samsung to produce faster, more efficient electronic devices.

“Basically any of your hard drives on your computer, or more likely in your phone, are made out of thin films devices,” he said. “Our group, especially, focuses on the read and write heads that record information and read the data once it’s been written.”

He has worked in the clean room for two years, but he said he hasn’t always been as comfortable with the process. Carton didn’t know much about thin films when he stayed after class to speak with Dr. Subhadra Gupta, professor of metallurgical and materials engineering and director of the facility, about signing up to work in the clean room after she mentioned the position during her lecture.

He’d interned with an air-conditioner manufacturing company the previous summer.

“A lot of the work was with sheet metal,” he said. “We were trying to bundle as many parts as possible on each sheet of metal in order to make it work efficiently. I didn’t mind the work, but it wasn’t a research job, and that’s what I really wanted to do.”

After being hired in the clean room, Carton signed up for a course on thin films. Between his coursework and working in the lab, he said he’s come a long way.

“I know how to do everything here, but I don’t always know why I’m doing it,” he explained. “I can make the whole device from start to finish; I just wouldn’t know what to put on it because I don’t know the theory behind it. But every week I can tell that I’m learning more and more. I didn’t think I would get to do so much hands-on stuff by myself. That’s what makes it exciting.”

“The scale of the devices we work with is so small that any dust or particulate can completely destroy them,”

– Michael Carton

He knows enough now to train new students coming to work. In a station in the far right corner of the lab, two new workers observed as Carton picked up a plastic box and took out a wafer.

By this stage in the process, graduate students have already deposited their carefully chosen patterns of metals onto the wafer. Carton’s job is to isolate a pattern out of the deposits by preparing the wafer for an etching machine that removes compounds not in a pattern.

“There’s not much visible difference, but there’s a chemical difference when you take it out of the machine,” Carton said, holding up the thin film for the two new student workers to examine.

Recently, Carton was hired for a summer internship researching the corrosion resistance of metals for Exxon Mobil Corp.

“I know for a fact that this experience working in the clean room helped me get my internship,” Carton said. “If I go to graduate school, it will be because this job has given me good experience.”

Of course, he hasn’t decided about graduate school yet. He said he’s keen on the idea, but he’d be tempted if he were offered a research job like his summer position with Exxon Mobil after graduation.

Until then, school and work will occupy most of his time, and when he’s not doing those things – baseball.

A version of this article appeared in the Undergraduate Magazine, published by the The University of Alabama’s Office of Academic Affairs in conjunction with University Relations.

Judah Martin is a journalism major at The University of Alabama. He is from Foley and serves as a student writer for the College of Engineering.